Writing , Content & Copywriting

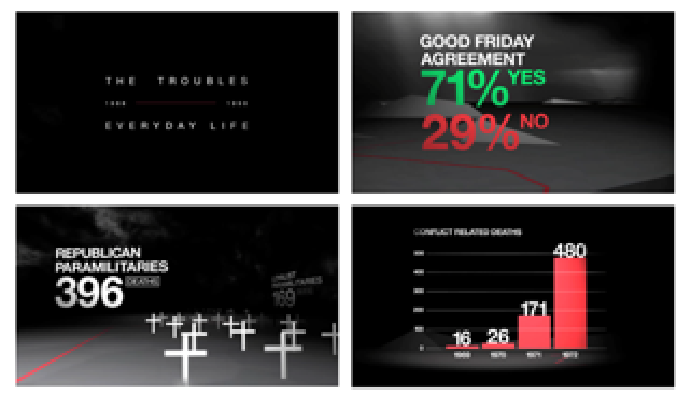

BBC Animated History of The Troubles

BBC Knowledge and Learning commissioned a series of seven historical documentaries to explain the events behind the Northern Ireland Troubles. Working with independent agency, Big Motive, the BBC editorial team and political expert, Prof. Jonathan Tonge, I created all seven scripts to accompany the animations.

View the seven short films here, with scripts narrated by BBC Radio 4’s Kathy Klugston.

Everyday Life

In the early Seventies, a visitor to Belfast might have thought its busy streets were much like any other in industrial Britain. A closer look and they’d see things were very different.

An armoured car with British soldiers, not just holding machine guns but aiming them. Queues of shoppers waiting to be body searched. Helicopters droning overhead. Police stations with high walls, guard towers and barbed wire along the nationalist Falls Road or the loyalist Shankill. Soldiers guarding police guarding streets.

To outsiders, this was an extraordinary way to live. But for the people of Northern Ireland it was everyday life. Before 1969, many working class Catholics and Protestants lived side by side in the same communities. They had much in common, not least the chronic unemployment and lack of decent housing.

But while the Protestant majority was politically and socially dominant, Catholics were marginalised and suffered constant discrimination. By the late Sixties, their protests for change were large and vocal. Violence followed as each community gave vent to its frustrations and prejudices.

Hostility and suspicion created harsh divisions. As Catholics and Protestants separated into their own communities, their migration became the largest population movement in Europe since the Second World War.

Violent paramilitary groups were a constant presence in these polarised areas and people quickly became desensitised to their brutality. By contrast, middle class suburbs were – for the most part – safe havens from the conflict.

“Fighting was in the news every night, but unless it touched your close friends or family, you didn’t pay it much mind,” one man remembers. “And if you didn’t live in working class Belfast or Londonderry, or near the trouble spots along the border, life was pretty idyllic.”

Frequent bombings prevented a normal social life, with pubs and bars as regular targets. By 6pm most town centres were deserted. Many turned to the arts to escape and the Belfast Festival was a beacon for grateful audiences, even though big acts rarely visited. Sport was popular too - inspirational even – with stars like George Best, Barry McGuigan and Mary Peters rising above sectarian divisions. But, depending on which team you supported or which game you played, entrenched hatred still found expression in the tribalism of sport.

Normal life did go on. People continued to get married and have families, though mixed marriages were rare. Many people left.

The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 brought peace and power sharing and laws that protect the rights of the individual, regardless of their background.

Even so, divisions remain. Many working classes areas in Belfast are still separated by peace walls and few children attend religiously integrated schools. The threat of violence from “dissident” paramilitaries lingers on.

But the two communities have edged closer together. And while the Troubles continue to cast their long shadow, everyday life in Northern Ireland is no longer so extraordinary.