Journal

Colhoun is Not a Common Name

Armistice 100 Days for the Imperial War Museum

On 11 November 1918, the First World War ended. After four years of unprecedented violence and devastation, Armistice was declared. But the stories and memories need to be renewed, lest we forget. Writers’ group 26 partnered with Imperial War Museums to mark this centenary in a unique way. I was invited along with 99 other writers to choose a subject from the war, and to tell that person’s story in poetry or prose in exactly 100 words. With the additional rule – start and finish with the same three words. This new form is called a centena.

You can read all the centenas on the Armistice project website.

I had two criteria for choosing a subject. One, that she would be a woman; and two, that she would have a direct and personal connection to me.

Annie Rebecca Colhoun was born in Derry in 1876.

My father and his family come from the same area in the North West of Ireland. So when I encountered the name, it seemed like fate knew what it was doing.

I was working late into the early hours. Bored by the project I was working on (something about pension trustees), I took a digital diversion into the internet, wanting to know who were the most decorated Irish women during the First World War.

There is some information, disappointingly little. Though I did stumble across a lovely book called The Glorious Madness: Tales of the Irish and the Great War authored by the rather marvellously named Turtle Bunbury.

Amazon was inviting me to “Look Inside”, and since hope of finishing the pension gig had all but evaporated, I scanned the list of contents and discovered a chapter entitled, “Nurse Colhoun and the Bombing of Vertekop”. Thank you for inviting me to look, Amazon.

Here’s a quick summary of her story.

On the morning of Monday 12 March 1917, a squadron of German aeroplanes bombarded the Macedonian railway station of Vertekop. A section broke away from the main body and flew towards the encampment of the 37th General Hospital. When the three aeroplanes first appeared overhead, the nurses would have felt reasonably secure given the prominently displayed red crosses painted on the tents. When the bombs dropped, Annie stayed at her post caring for all the wounded men and another fatally wounded nurse. Even when she herself was hit by splinter from the bombing, she continued to work and was responsible for saving many lives. Four orderlies and two nurses died that day.

Here’s an extract from Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps:

“For conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty during an enemy air raid. She attended to, and provided for the safety of, helpless patients. She was assisting Staff Nurse Dewar when the latter was fatally wounded, and although the tent was full of smoke and acrid fumes, and she had been struck by a fragment of bomb, she attended to Staff Nurse Dewar and also to the case of a helpless patient.”

Annie Colhoun was awarded the Military Medal, the French Croix de Guerre (bronze star), the Serbian Gold Medal and Nine Blue Chevrons.

She died in 1956.

I don’t yet know if we are directly related. That spelling of our surname is unusual so I suspect there is a family connection; though neither my father nor his cousins had heard of her. I’ll continue to do that research. For now I am content to share my uncommon surname with this uncommonly brave and principled woman, and one hell of a role model for the Colhouns who came after and those yet to come.

NB As a rather lovely surprise, this centena was Highly Commended in the 26 Writer's Awards 2019.

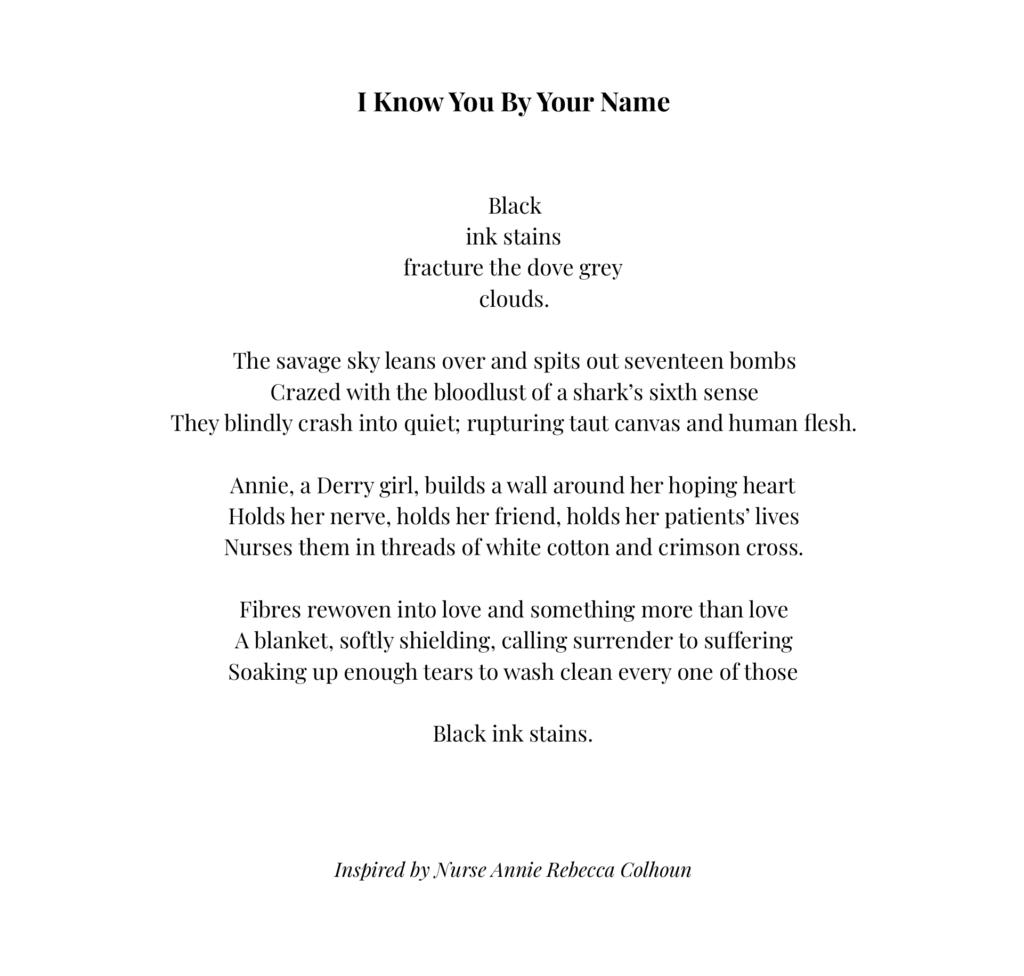

Nurse Annie Rebecca Colhoun.

Photo provided by Turtle Bunbury.